"Picture her to yourself, and

ere you be old, learn to LOVE and to PRAY!"

~William Makepeace Thackeray, Vanity Fair

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Dorinda at her Glass

by Mrs. Leapor

Toast of the town, and triumph of the plain;

Whose shining eyes a thousand hearts alarm'd,

Whose wit inspired, and whose follies charm'd:

Who, with invention, rack'd her careful breast

To find new graces to insult the rest,

Now sees her temples take a swarthy hue, And the dark veins resign their beauteous blue;

While on her cheeks the fading roses die,

And the last sparkles tremble in her eye.

Bright Sol had drove the fable clouds away,

And chear'd the heavens with a stream of day,

The woodland choir their little throats prepare,

To chant new carols to the morning air:

In silence wrapp'd, and curtain'd from the day,

On her fad pillow lost Dorinda lay;

To mirth a stranger, and the like to ease,

No pleasures charm her, nor no slumbers

please.

For if to close her weary lids she tries,

Detested wrinkles swim before her eyes;At length the mourner rais'd her aking head,

And discontented left her hated bed.

But sighing shun'd the relicks of her pride,

And left the toilet for the chimney side:

Her careless locks upon her shoulders lay

Uncurl'd, alas! because they half were gray;

No magick baths employ her skilful hand,

But useless phials on her table stand:

She flights her form, no more by youth inspir'd,

And loaths that idol which she once admir'd.

At length all trembling, of herself afraid,

To her lov'd glass repair'd the weeping maid,

And with a sigh address'd the alter'd shade.

Say, what art thou, that wear'st a gloomy form,

With low'ring forehead, like a northern storm;

Cheeks pale and hollow, as the face of woe,

And lips that with no gay vermilion glow?

Where is that form which this false mirror told

Bloom'd like the morn, and shou'd for ages hold;

But now a spectre in its room appears,

All scar'd with furrows, and defac'd with tears;

Say, com'st thou from the regions of despair,

T0 shake my senses with a meagre stare

Some straggling horror may thy phantom be,

But surely not the mimick shape of me.

Ah! yes~~~ the shade its mourning visage rears,

Pants when I sigh, and answers to my tears:

Now who shall bow before this wither'd shrine,

This mortal image that was late divine?

What victim now will praise these faded eyes,

Once the gay basis for a thousand lyes?

Deceitful beauty~~~ false as thou art gay,

And is it thus thy vot'ries find their pay; This the reward of many careful years,

Of morning labours, and of noon-day sears,

The gloves anointed, and the bathing hour,

And soft cosmetick's more prevailing pow'r?

Yet to thy worship still the fair-ones run,

And hail thy temples with the rising sun;

Still the brown damsels to thy altars pay

Sweet-scented unguents, and the dews of May;

Sempronia smooths her wrinkled brows with care,

And Isabella curls her gristed hair:

See poor Augusta of her glass afraid,

Who even trembles at the name of maid,

Spreads the fine Mechlin on her shaking head,

While her thin cheeks disown the mimick red.

Soft Sylvia, who no lover's breast alarms,

Yet simpers out the ev'ning of her charms,

And though her cheek can boast no rosy dye,

Her gay brocades allure the gazing eye.

But hear, my sisters, hear an ancient maid,

Too long by folly, and her arts betray'd;

From these light trifles turn your partial eyes,

'Tis fad Dorinda prays you to be wise;

And thou, Celinda,'thou must shortly feel

The sad effect of time's revolving wheel;

Thy spring is past, thy summer fun declin'd,

See autumn next, and winter stalks behind:

But let not reason with thy beauties fly,

Nor place thy merit in a brilliant eye;

'Tis thine to charm us by sublimer ways,

And make thy temper, like thy seatures, please:

And thou, Sempronia, trudge to morning pray'r,

Nor trim thy eye-brows with so nice a care;

Dear nymph, believe 'tis true, as you're alive,

Those temples stew the marks of fifty-five.

Let Isabel unload her aking head

Of twisted papers, and of binding lead;

Let sage Augusta now, without a frown,

Strip those gay ribbands from her aged crown;

Changed the lac'd flipper of delicious hue

For a warm stocking, and an easy shoe;

Guard her swell'd ancles from rheumatick pain,

And from her cheek expunge the guilty stain.

Wou'd smiling Sylvia lay that hoop aside,

'Twou'd shew her prudence, not betray her pride:

She, like the rest, had once her flagrant day,

But now she twinkles in a fainter ray. Those youthful airs set off their mistress now,

Just as the patch adorns her autumn brow:

In vain her feet in sparkling laces glow,

Since none regard her forehead, nor her toe.

Who would not burst with laughter, or with spleen, At Pruda, once a beauty, as I ween?

But now her features wear a dusky hue,

The little loves have bid her eyes adieu:

Yet she pursues the pleasures of her prime,

And vain desires, still unsubdu'd by time;

Thrusts in among the frolick and the gay,

But shuts her daughter from the beams of day:

The child, she says, is indolent and grave,

And tells the world Ophelia can't behave:

But while Ophelia is forbid the room,

Her mother hobbles in a rigadoon;

Or to the found of melting musick dies,

And in their sockets rolls her blinking eyes;

Or stuns the audience with her hideous squall,

While scorn and satire whisper through the hall.

|

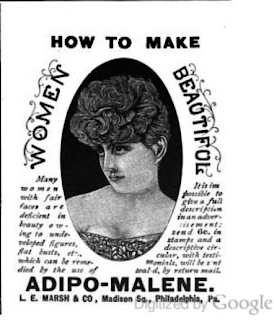

| image source~ wiki commons |

Hear this, ye fair ones, that survive your charms,

Nor reach at folly with your aged arms;

Thus Pope has sung, thus let Dorinda sing;

"Virtue, brave boys, 'tis virtue makes a king."

Why not a queen ? fair virtue is the fame

In the rough hero, and the smiling dame:

Dorinda's soul her beauties shall pursue,

Though late I see her, and embrace her too:

Come, ye blest graces, that are sure to please,

The smile of friendship, and the careless ease;

The breast of candour, the relenting ear,

The hand of bounty, and the heart sincere:

May these the twilight of my days attend,

And may that ev'ning never want a friend,

To smooth my passage to the silent gloom,

And give a tear to grace the mournful tomb.